Maybe 15 years ago, I came across a very old wooden chest — perhaps three feet high, the kind you might store quilts inside — at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Although relatively unassuming at first glance, that piece of furniture has since come to occupy more space in my mind than almost any other object I’ve encountered at a museum.

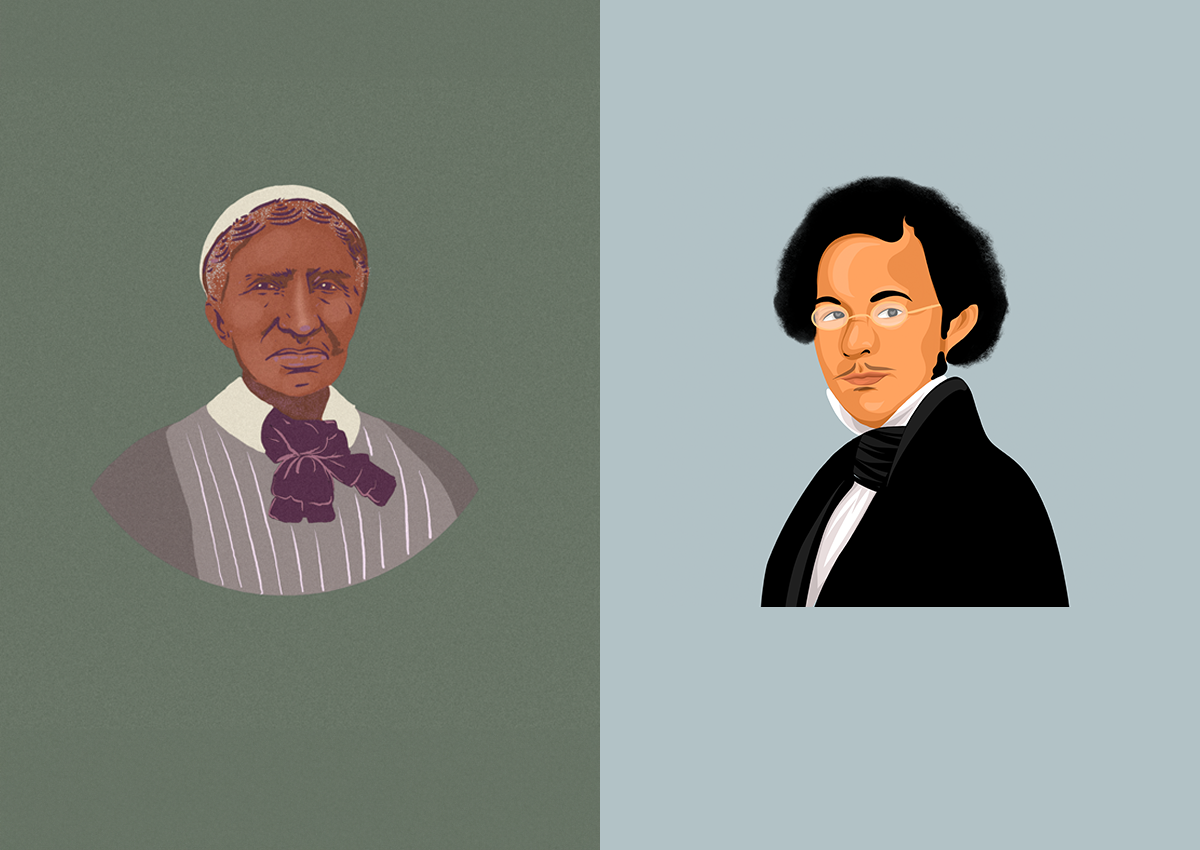

The chest came from somewhere in colonial Latin America. On its lid was a kind of grid of family portraits. Each family portrait depicted a mother, a father, and their child. Below each portrait, a caption spelled out which caste the child had been born into, depending on how much Black, white, or Indigenous blood flowed through their veins. The precise formulas on the painted chest didn’t lodge themselves automatically in my mind the way the images did, but I later learned that the painting which caught my eye is part of a larger tradition of 18th-century casta art, which chronicled the social strata of Latin America at that time. Most casta paintings have 16 racial categories. Beneath the image of a Spanish father and Indian mother, for instance, one might find the word mestizo or “half-blood.”

At the time, I was mostly struck by how extensive the taxonomy was — and also by how jarring it was to see people grouped into hierarchical categories according to the color of their skin. As someone with an Italian grandfather and a Mexican grandmother, I took a moment to figure out where I would have stood in the rankings. And then I moved on to another room in the museum, unaware that the chest would reappear in my mind’s eye for years to come.

When I studied African American literature in graduate school and encountered the “one-drop rule,” there it was again — the casta chest. The one-drop rule, which was unique to the United States, declared that any person with even one drop of Black blood was Black. Although the one-drop rule had only a brief and fraught existence as a legal means of classifying race, it has persisted for much longer as a cultural one.

The stark black-and-white binary of the one-drop rule stands in depressing contrast to the casta paintings. It is brutal in its simplicity, which takes into account only two races. In the legal fiction and cultural narrative put forward by the one-drop rule, the indigenous population of the United States simply doesn’t exist. It has been completely eliminated.

The one-drop rule is brutal, too, in the way that it isolates individuals, cuts them from their own families and — when used to justify chattel slavery — from even the larger family of the human race. The child with a drop of Black blood, according to the one-drop rule, is no longer necessarily a child at all, but mere property. The one-drop rule made marriage between races taboo in the United States — or even a crime. The last miscegenation laws were struck from the books only in 1967.

In colonial Latin America, by contrast, intermarriage between races was met with at least some degree of legal, ecclesiastical, and cultural approval — or else we wouldn’t have casta paintings. In them, one finds a tolerance for complexity, for the complicated and often unexpected reality of human love. Beneath that, one can also discern a tacit recognition of an even more fundamental reality, which is that human beings — by virtue of both biological necessity and divine design — are always embedded in families. This acknowledgment of the centrality of families has, hauntingly, no American corollary in conversations about race.

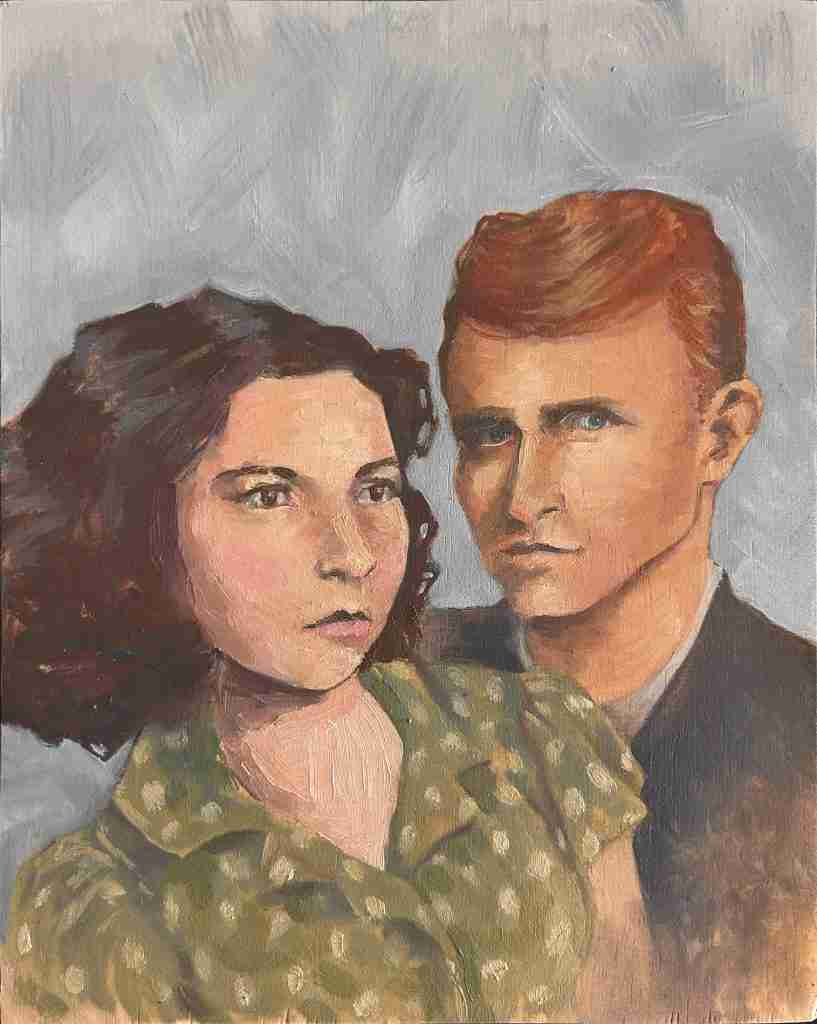

I should pause here to say that I am not trying to endorse the racial hierarchy of colonial Latin America. Nor am I trying to ignore the complicated legacy of race in places other than the United States. What I am doing is observing that the story of a dark-skinned woman and a fair-skinned man falling in love, marrying, and having children is the story of my own grandparents in Mexico City after World War II. The story found on casta paintings is also theirs, and, to some extent, mine. I find it impossible to imagine my grandfather faced with the choices left to a man with even the best intentions in the 18th-century United States: physical intimacy, without the sanctity of marriage; a concubine, not a wife; children loved but not recognized. Yet we know that such women and children existed and somehow endured.

Why the United States, seemingly alone among the Americas, should have prized subjugation over love and life, bothered me in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and bothers me still.

***

Historically, my anecdotal surveys of fellow professors suggests, timing alone accounts for at least part of the discrepancy between the United States and the rest of Latin America. Between the establishment of the first Spanish colonies in the late 1400s and the American Revolution three centuries later came two important developments in the history of ideas.

The first was the rise of capitalism, an economic system that prioritizes the accumulation of capital — an abstract good, until it is turned back into concrete products and services — and can, when unchecked, tend to look the other way at harmful consequences that commonly accompany that goal, including wealth inequality, class conflict, and corruption. Scottish economist Adam Smith published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in March 1776; the Declaration of Independence was signed six months later. One doesn’t have to look very hard to find examples of how we as a nation — essentially born in the same year as free-market economics — consistently prioritize the bottom line over quality of life today. The efforts of the gun lobby are one contemporary example of the United States privileging money over lives; the prohibitive cost of prescription medications another; the ubiquity of technology, despite mounting evidence of its harmful effects, especially on the young, a third.

The second development was the Enlightenment. If capitalism gave the United States Mammon as a master, then the Enlightenment played a part in drawing us further away from the master we consequently chose not to serve: God. Enlightenment thought emphasized the primacy of reason and science, advocated for the separation of church and state, and abhorred religious intolerance — sometimes in its own intolerant way, as with Voltaire’s famous admonition to do away with religious bigotry and superstition: “Ecraser l’infame!” (“Crush the infamous thing”).

The Enlightenment gave the Western hemisphere encyclopedias and democratic revolutions, but it also left us with weakened religious authorities and a diminished belief in souls. The earliest Spanish conquistadors had a pope as well as a monarch to report to back home — and their behavior was terrible enough at times. Later colonists had all the same incentives as before to pillage the New World, but no longer any reason to try and save the inhabitants they found there, or to win their souls for God.

***

Today, racial data in the United States is collected with more nuance than the one-drop rule, though less than a casta painting. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget currently requires a minimum of five categories — White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander — and also recognizes (in the words of the U.S. Census Bureau and as a testament to the varied social world captured in casta paintings) that “people who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race.”

What exactly we ought to do with that data once we collect it is hotly contested. Five years ago, DEI programs rocketed to the top of HR agendas across the country. In January, they were swiftly declared illegal in a presidential executive order and banished from the federal government. This rapid swing of the pendulum from one extreme to another is unlikely to be the last such shift we see in our lifetimes.

Both sides of the debate appear to be motivated largely by fear, fear that one group or another will be unfairly disadvantaged or excluded, whether by the existence of DEI programs or by their dissolution. And perhaps it’s no wonder that we are anxious today in the United States. Existing meritocratic systems of education and employment seem to be breaking down. In the face of an unpredictable future, there are lots of reasons why we might instinctively want to reach for a sizable piece of what appears to be a shrinking and increasingly unstable pie.

Both sides of the debate also seem to share a deeper fear below that one. An existential fear that we might be passed over somehow, that we will deserve something and not get it, or need help and not receive it. A fear that we might be lost — unseen, unvalued, and unloved, and that this loss will be all the worse if it results from something we never chose and could not help. This fear, too, has roots in reality that make it compelling and hard to dislodge. Often enough, we are overlooked and treated unfairly by flawed people and flawed systems.

And yet, I choose — not glibly but deliberately, because those fears are mine, too, sometimes — to take Jesus at his word when he promises, “Peace I leave with you, My peace I give to you; not as the world gives do I give to you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid” (John 14:27). And I take his promise to mean that the right way forward, for Christians, can never come from a compass oriented around fear.

Might casta paintings contain a hint about how to reorient these debates?

Is there any opportunity, in our conversations about race and gender and sexuality and every other bodily difference that presents us with a pretext for division — is there any opportunity in all of these contentious subjects to talk about families, too? To shift away from thinking in terms of labels and toward lineage?

After all, none of us rolled off the assembly line with a machine-determined amount of melanin. We each came into the world as a single link in a long chain made up of people: parents and grandparents and great-great-great-great-great-grandparents whose faces and names have been long forgotten, but whose skin or eyes or hair may, for all we know, have been an exact replica of our own. I had my grandfather’s mischievous smile when I was young. My daughter has it now. Who else shared that same eye-twinkle, that same grin?

The appeal of labels is convenience. Computers can easily track them. If I have the most diverse pile of beans — some kidney beans, some lima beans, some lentils — I can readily boast about that in my annual report. But there is no scriptural basis for thinking that human beings were made to become fodder for computer codes or annual reports.

By contrast, there are several moments in the Bible one might point to and argue that human beings were created as the building blocks out of which families are made. In Genesis, God says, “It is not good that the man should be alone” (2:18). At the wedding feast at Cana, Jesus affirmed the importance of marriage and raised it to a sacrament (John 2:1-12). Against the protests of his own busy disciples — who were perhaps eager to get on with the work of healing the sick and exorcising demons, maybe even a little proud of how many such miracles they performed in a day — he insisted upon the importance of dropping everything to bless children: “Let the little children come to Me, and do not forbid them; for of such is the kingdom of heaven” (Mat 19:13-15).

Ultimately, each one of us is personally invited — should we choose to accept the honor and the cross — to become nothing less than an adopted child of God, a brother or sister in Christ, a priceless member of the most beautiful and enduring family imaginable. Not every corporate DEI workshop, should they survive, will want to phrase things in those terms. But both diversity and belonging are built into the Christian understanding of this world and the one to come, from the Trinity on down. If there are ways to share the peace of Christ in this realm, I hope we will find them.

***

Maybe all problems are at root theological ones. Half a century ago, two 20th-century American writers — one Black and one white — argued as much in their analysis of race. Both ultimately diagnosed unhealthy attitudes toward skin color in the United States as symptoms of a deeper metaphysical problem: a kind of national unwillingness to acknowledge the reality of sin and death.

From the start, the United States has been driven by a vision of exceptionalism. The New World held out the promise of a blank slate, a chance to leave behind all the corruption and wickedness of the Old World and start afresh. It was our Manifest Destiny, both obvious and certain, to build a new, exemplary, liberal democratic empire that would stretch across an entire continent. (Like the one-drop rule, this narrative of American exceptionalism is tragically predicated on the complete elimination of Indigenous peoples, in real life and in memory.) This triumphalism is what allows us to look back at Puritan attorney John Winthrop’s famous exhortation that the new colony in Boston was to be “as a city upon a hill,” with “the eyes of all people … upon us,” and to recall it as a boast. Actually, it was also a warning.

Winthrop continues, “So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a byword through the world.”

To think that good intentions and a fresh start are enough to save anyone from human nature is foolish. But we Americans have a long history of making that mistake in matters both foreign and domestic. Novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne gave the lie to this understanding with a memorable image in 1850. On the first page of The Scarlet Letter, he reminds us that “the founders of a new colony, whatever Utopia of human virtue and happiness they might originally project, have invariably recognized it among their earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as the site of a prison.”

Hawthorne himself was a descendent of Puritan settlers. In his early 20s, he actually added a w to his original surname of Hathorne in order to distance himself from his family’s complicated legacy. Americans today would do well to heed Hawthorne’s reminder — that although sin and death were conquered once and for all on Calvary, they still lurk about and will rule over our hearts and our cities until we deliberately ask Jesus to govern us instead. We are not yet in the New Jerusalem. In this pilgrim life, we must expect that prisons and cemeteries, like the poor, will always be with us.

Our national refusal to believe — again, in a half-formed, tacit way, occurring on some deep level of the collective unconscious — that to be human is to be both capable of evil and bound to death leads us into all sorts of problems, including with race.

Lacking a strong sense of evil, Americans aren’t always on guard against our own bad impulses. Optimistic about technology’s capacity to cure diseases — and perhaps even stave off death indefinitely — we delay our entrance into moral maturity. Existential grappling can always be put off until tomorrow.

James Baldwin posits that precisely this kind of refusal to engage deeply with difficult and frightening topics — including the most frightening one of all, death — is the cause of pretty much every problem that has ever existed, American or otherwise, race-related or otherwise.

Born to a single mother in Harlem in 1924, Baldwin later took the last name of his stepfather, a Baptist preacher whose “devotion to God was mixed with a hope” (in the words of one biographer) that “God would take revenge on white people for him, preferably very soon.” Baldwin ultimately rejected the vindictive version of Christian faith that had loomed so large in his youth, although not until after he had absorbed much of Christianity’s language and its strongly held convictions about both justice and mercy. In adulthood Baldwin also rejected his stepfather’s racial animus, later saying that a young, white, female schoolteacher from the Midwest named Orilla “Bill” Miller — who mentored Baldwin in elementary school and took the future playwright to his first live performance, an all-Black staging of Hamlet by Orson Welles — was the reason he “never really managed to hate white people.”

Baldwin writes in The Fire Next Time (1963), “Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.” In his essays, Baldwin himself never seems to be afraid, of death or anything else. His calm, steady, compassionate courage makes him wonderful company if you have time to read the whole book. Elsewhere, he says that “to defend oneself against a fear is simply to insure that one will, one day, be conquered by it; fears must be faced.”

Facing a fear of death, for Baldwin, involves a deliberate commitment to make the most of whatever time one has left, and to “trust and celebrate what is constant — birth, struggle, and death are constant, and so is love, though we may not always think so.” By honoring these eternal verities, one is renewed and made free.

But, Baldwin continues, “renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant that are not — safety, for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope — the entire possibility — of freedom disappears.” Those white Americans who “do not believe in death,” Baldwin concludes, are themselves unfree — in that they are controlled by their fear — “and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.”

Three years after Baldwin published The Fire Next Time, novelist Thomas Pynchon came to a similar conclusion in an essay about the Watts Riots in Los Angeles for the New York Times. Born on Long Island in 1937, Pynchon is — as Baldwin was — a native New Yorker. In covering the Watts Riots, he argued that the divide between Black and white citizens of L.A., which was made visible by outright violence, was actually a consequence or symptom of a larger phenomenon, in which the wealthy, mostly white Angelenos in the creative class invented new ways to evade the harsher aspects of reality, including death.

“While the white culture is concerned with various forms of systematized folly — the economy of the area in fact depending on it,” Pynchon writes, “the black culture is stuck pretty much with basic realities like disease, like failure, violence and death, which the whites have mostly chosen — and can afford — to ignore.”

A half-century later, opportunities for evading reality today are devastatingly ubiquitous. Certainly, California is churning out more “systematized folly” than ever before. And if Hollywood promised only tacitly that we could escape reality for a bit (as viewers) and live forever (as movie stars), then Silicon Valley has made those promises explicit, in banal forms like Facebook and more exotic ones like those associated with the transhumanism movement.

Pynchon goes on to observe that between the two communities there lies a deep and uneven chasm, thanks to one-way cultural integration and two-way geographical segregation. “The two cultures do not understand each other,” he writes, “though white values are displayed without let-up on black people’s TV screens, and though the panoramic sense of black impoverishment is hard to miss from atop the Harbor Freeway, which so many whites must drive at least twice every working day.”

This lopsided dynamic — the waters of (mostly) white-manufactured unreality in which all Americans have been forced to swim, while the wealthiest and often whitest ones could, until relatively recently, choose whether or not to opt in to any kind of meaningful awareness of Black reality — surely gives vehemence and urgency to dynamics around race and diversity today, whether these play out through riots (as in Ferguson, Missouri) or through waves of activism.

Baldwin was right: Fears must be faced. If our national narrative has left us with no way to account for fear and failure and death, then it will also leave us bereft of courage and redemption and resurrection.

A few years ago, on a visit to Monticello, I listened as a tour guide cheerfully pointed out the home’s rounded walls and explained that Thomas Jefferson had had them specially made because he hated shadows. Something in me recoiled at this fact; it seemed to explain a lot, even too much.

***

I don’t have a solution, and I would be wary of those who feel sure that they do. A sound way forward for our nation, whatever that looks like, will not be determined by any one person or group, but will require dialogue. My strongest sense is that we must find a way to tell ourselves a fuller, truer story, about the shadows and the points of light in this nation’s history, and about the places where they sometimes even coexist.

Christianity can provide a good counterweight to the present moment, because in its best forms it upholds a system of value that has nothing to do with money; it emphasizes the primacy of the family and the individual conscience; and it models a version of triumph that kneels down to wash another’s feet.

Art, too, can play a role in shifting perspectives imperceptibly toward the kind of vision that could heal us.

Seven years ago, I read books on race by James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates with cadets at the United States Military Academy. West Point is, like the NYC subway, an institution whose vast racial diversity puts casta paintings to shame. In my time there, at least once I stood in an empty classroom after a seminar and marveled that I had been entrusted with the sons and daughters of people whose lives were very different from mine. (I still marvel at this fact, even more so retroactively, now that I have a child of my own and realize just how much love, time, patience, and other resources were invested in those students long before they got to my classroom.)

The cadets from the South had names like Brock and Boomer, and would’ve called me “ma’am” even if they weren’t in the Army. The ones from the Dakotas could look at a field and see millions of dollars where I would just see leaves. Only two were shorter than me — though their heights were no impediment to success at competitive boxing and jiu jitsu — and one, a basketball player, left writing so high up on the chalkboard that I had to jump after class to erase it, which made me realize, with a shock, that for all the training in empathy literature had given me, I have absolutely no idea what it is like to be tall.

They came from all over, and they were mysteries to me, and looking back I can admit I was afraid of them to some degree at first. In retrospect, my fear was mostly self-directed (Are they judging me as a teacher? Am I, in fact, doing a terrible job as their teacher?). As I got my teaching feet under me, found lesson plans and assignments that worked, and felt more secure in my ability to help them with their reading and writing, I was freed up to be curious. Once I knew where I stood, I could afford to be interested in what the view was like from wherever they stood. But first I had to look within, and get my own affairs in order, before I could see more clearly what (and who) was without.

I don’t mean to downplay the importance of race when I say that the young white man from Tennessee whose accent charmed his peers — always, always, they nominated him to read passages aloud — was and remains as unfathomable to me as the soft-spoken young Black woman who loved playing rugby and came in smiling through a split lip on more than one occasion to prove it. But it’s true. Both were a delight to have in class precisely because they were not like people I had met before.

I truly wish now that I could show you what is in my mind when I think of those students, mostly smiling, sometimes (given the rigors of life at a military academy) asleep, often polite, just as often impish; or what is in my notebooks, all the funny and brilliant things they said. I wish I could show their parents, too: How clever and hilarious and brilliant your children are. How some are incredibly smart but have uncomprehending resting faces, so you mustn’t judge anyone on first impressions; how some look like they are always on the verge of laughing, and it makes you want to say something funny so that they will; how some are natural sheepdogs who look out for the quiet ones and find a way to get their guard down and bring them into the group; how some make a sudden hand motion to signal “my brain is exploding” when a story or poem reveals its meaning to them. Most classrooms, or at least more than you’d expect, contain at least one person like me, who is phenotypically white but (in my own, non–Census Bureau approved verbiage) secretly Mexican.

Maybe it was by virtue of my phenotypical whiteness that I remember race as being present but not divisive. Maybe it was because we always had a shared mission, at the institutional level or the level of a single text, to unite us. Maybe I am remembering wrong, or perhaps I didn’t understand what someone was going through at the time. But I have never seen so many shades of human being anywhere else (except, again, for the New York subway), and I have never loved any job in quite the same way as I loved teaching first-year literature and composition at West Point.

When we read Baldwin, one cadet who is African-American — from my hometown of Milwaukee, although I didn’t know that at the time — put his hands down on the desk in frustration and said that he didn’t even want to start discussing The Fire Next Time, because we only had 50 minutes to talk and we were too clumsy and we would never do it justice. He was right, I replied: We never could do it justice in the course of the two 50-minute class periods assigned to the book. We would surely miss a lot, and in dealing with a sensitive issue, we’d probably say the wrong things sometimes. But we also wouldn’t do it, or ourselves, justice by not trying at all. Aristotle, I added for good measure, says that ignorance and viciousness are the same thing, and that the vicious person simply doesn’t know any better. Could we, perhaps, I asked, if a classmate said the wrong thing, try to assume that he or she was not vicious, but simply in need of understanding? Sure enough, not a minute later, the wrong thing was indeed said, but we recovered, and the discussion went on.

Whatever was with us in the room that day — some patience, some trust, some grace — it worked. Whenever Americans speak to one another with curiosity and compassion, about our past and our future, about what unites and divides us, I will pray it will be there, too.

***

Conversations about race in contemporary America are a swiftly moving target. I’m not sure how much of what I heard from young people in 2018 is directly relatable today. I’m not sure whether a sentence written or revised in February 2025 will be relevant in late March, when this magazine lands in mailboxes.

But I do vividly remember one particular day when cadets and I somehow wound around to the discovery that pretty much everyone in the classroom felt unwelcome. West Point’s traditional demographic of white males from the South felt unappreciated and even somewhat resented; they were sure that as they advanced into upperclassmen they would be overlooked for key leadership positions in favor of more “diverse” cadets. Female cadets and cadets of color, meanwhile, felt that perhaps they had been selected for the wrong reasons, or that maybe it was all a sham and that they weren’t truly welcome. Unsavory posts on a then-current social media app, YikYak, periodically cropped up to inflame such fears. At the very least, such posts confirmed that racial and sexual tensions hadn’t entirely disappeared. They had just gone underground, to simmer and fester and come up again in new, unpleasant, and dangerously anonymous digital ways.

The day when everyone felt unwelcome really threw me. Thinking of every Episcopalian church bulletin I’d seen in approximately 15 years of churchgoing, I looked at the faces around the room and said slowly, “I am glad that you are here.” And it was true. I was.

When the cadets and I tried to work out who exactly might really be welcome at West Point, the best we could come up with were the people featured on the website. Fast-forwarding to the present moment, I wonder who feels welcome at West Point today, and what’s being said on whatever social media app has replaced YikYak.

On January 20, 2025 — the day of his Inauguration and also Martin Luther King Jr. Day — President Donald Trump issued an executive order terminating “illegal DEI and ‘diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility’ (DEIA) mandates, policies, programs, preferences, and activities in the Federal Government, under whatever name they appear.” Two weeks later, the United States Military Academy announced the abrupt closure of 12 cadet clubs with a focus on ethnic or gender identity, including the Latin Cultural Club; the Native American Heritage Forum; three societies for aspiring engineers, aimed at Black, Hispanic, and female cadets, respectively; clubs for Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Asian-Pacific cadets; and Spectrum, a club first formed at West Point as a gay-straight alliance in 2011, when President Bill Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy was repealed by President Barack Obama. The memo to the directorate of cadet activities disbanding the clubs indicated that their websites, too, must be taken down. When both the problem and the solution — or the solution and the problem, depending on how you want to look at DEI initiatives — send a message to flesh-and-blood human beings that they are unwelcome, something has gone terribly wrong.

***

In the wake of the February 4 memo, my former officemate at the United States Military Academy, Lt. Col. Trivius Caldwell, posted an excerpt from a talk that novelist Ralph Ellision gave at West Point in 1969.

A decade older than James Baldwin and two decades older than Thomas Pynchon, Ellison had come to West Point to speak to first-year cadets (nicknamed “plebes”) about his most famous novel Invisible Man. The book won the National Book Award for fiction in 1953. In 1969, it ended up on the syllabus for a mandatory introductory literature course at West Point. Ellison’s remarks in 1969 are uncannily, even providentially, related to the question that set this essay in motion. Invisible Man, he told the cadets, began with a phrase that floated into his head as he sat in an old barn in Vermont looking out at a mountain: “I am an invisible man.” And with a sense that,

there was a great deal about the nature of American experience which was not understood by most Americans. I felt also that the diversity of the total experience rendered much of it mysterious. And I felt that because so much of it which appeared unrelated was actually most intimately intertwined, it needed exploring. Indeed, I believed that unless we continually explored the network of complex relationships which bind us together we would continue being the victims of various inadequate conceptions of ourselves, both as individuals and as citizens of a nation of diverse peoples. For after all, American diversity is not simply a matter of race, region, or religion. It is a product of the complex intermixing of all these categories.

Reality, in Ellison’s view, was so complicated that its reach would always exceed our imaginative grasp. The Black experience in Oklahoma City, where Ellison was born, was different from the Black experience in Gary, Indiana, where his mother briefly tried to start a new life after his father’s death. Both experiences were different from the Black experience in Harlem, where Ellison moved in 1936, at the age of 23.

He aimed, as a novelist, to discern from the unfathomable complexity of individuals’ lived human experience a set of patterns, rules, and truths from which readers might glean some nuggets of wisdom that could illuminate their own lives. (Aristotle, in the Poetics, calls such truths “universals.”) And so Ellison’s emphasis was on reduction. Our emphasis today — as our increasingly online lives steer us away from the richness of experience and toward binaries, categories, emojis, the pitiable flattening of the world into computer code — might be to push in the opposite direction, toward an expansion of imagination when it comes to considerations of race in America.

What we can agree on, in Ellison’s day and in our own, is that the complicated middle, which is impossible ever to pin down fully, is where we as Americans and as individual human beings must try to live. “In these United States, the crucial question is not one of having a perfect society,” Ellison told cadets. “Rather it is to keep struggling, to keep trying to reduce to consciousness all of the complex experience which ceaselessly unfolds within this great nation.”

“If I managed even a little of that in the book,” Ellison concluded, “then I think the effort worthwhile.”

As a professor at West Point, I felt that my efforts as a teacher were always worthwhile. I was heartened in particular by the thought that any good I did would, if all went well, benefit not only the students directly in front of me, but also the soldiers they would someday lead. I felt then the same exhilaration that I feel now when a charity promises me that corporate matching grants will increase my small contribution by three or five or eight times as much and go much further than my modest gift alone could go. Any clarity in thinking, any nuance, any ability to put oneself into the perspective of another that cadets developed in my English classes would pay dividends the moment they were assigned a platoon.

When I think of students — or anyone, really — through the lens of a casta painting, I feel much the same. We are each of us a daughter or son, a mother or father (or possibly a future parent), a sister or brother, a friend. We cannot see in advance how the ripple effect of our daily actions will flow through those webs of families and communities. We can’t even see how it unfolds in real time. We won’t know until the last judgment how it will all play out. But by putting individuals back into a relational context, we gain a glimpse, perhaps a mere hint, of those ripples and the complicated ways in which good (or its lack) are always amplified, even to the ends of the earth.